Are ‘micro-apartments’ converted from offices the respond to the housing crisis?

Are ‘micro-apartments’ converted from offices the respond to the housing crisis?

You’ve heard of tiny houses. What about tiny, tiny, apartments?

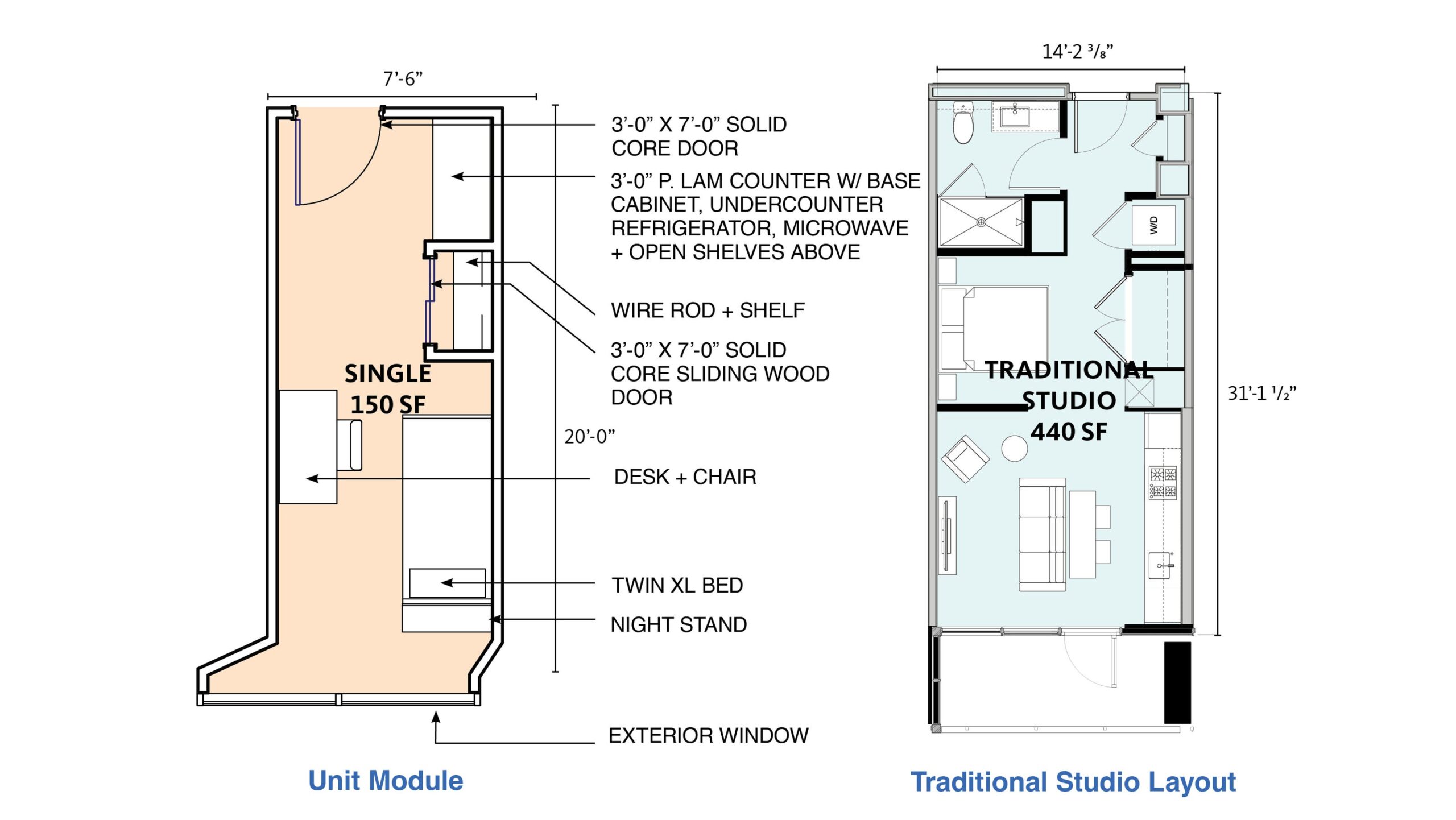

A recent proposal to address the housing crisis would convert vacant office space in many American cities to deeply affordable apartments for rent. The catch: in order to be so cheap, the units would be 150 square feet at the most, about the same size as the average college dorm, and meant mostly for sleeping. Living rooms, kitchens, bathrooms, and laundry facilities would be shared with others on the same floor.

The concept for tiny private units within communal spaces isn’t recent: single-room occupancy dwellings have been around for centuries, and in the years just before the pandemic, handfuls of “co-living” buildings around the country had a instant. recall “WeLive” from WeWork?

But the recent proposal, from the Pew Charitable Trusts and architecture-design firm Gensler, aims to marry the traditional concept with the relatively recent glut of vacant office spaces – and the enormous barriers to converting them to standard economy-rate one, two, or three-bedroom homes.

About 20% of office buildings around the country are still vacant four years after the COVID pandemic sparked a rush to work-from-home practices – and that distribute is much higher in some cities. Yet the country also faces a dearth of affordable housing estimated to be in the millions of units.

Buy that aspiration house: view the best mortgage lenders

More:Homeownership used to cruel stable housing costs. That’s a thing of the history.

Concentrating plumbing and kitchens in the center of each floor (where they usually already are in offices), rather than in each unit, saves about 25-35% of the expense of construction versus other office-to-residential conversions, the update reckons. “Because the microapartments are narrow and deep, every resident would have a large window, but each floor would accommodate roughly three times as many units as a typical apartment building,” the writers declare.

The update assessed how feasible it would be to perform these conversions in three cities. Seattle, Denver, and Minneapolis were chosen because they all have high median rents, lots of vacant space in downtown offices, and a high rate of homelessness and “housing insecurity,” which means trouble affording housing consistently. All three cities also have what the writers call “no significant existing regulatory barriers.”

The image above shows a proposed apartment in Denver, which would expense about $850 – less than half the current median rent in the city of $1,771.

Pew and Gensler depend the apartments will appeal to a broad range of tenants: elderly residents who may no longer be able to live at home, people who have recently relocated to a recent city, even governments looking for an affordable alternative for homeless residents. Residents would require to pass through safety and only have access to the floors where they live.

“This isn’t solving every issue out there” said Alex Horowitz, assignment director for the housing policy initiative at Pew, in a press briefing. Still, Horowitz argues that these “microapartments” add housing supply to a economy at the most affordable worth point, which is the one that’s hardest for developers to satisfy.

Creating affordable housing in the heart of urban downtowns would also assist revitalize many commercial areas that have struggled since the pandemic, Horowitz said. In addition, it would assist reduce greenhouse gases by encouraging residents to receive community transit or to walk to nearby jobs, rather than drive.

From initial conversations with developers and investors about the schedule, Gensler and Pew have determined there’s plenty of gain in the concept, but “the devil is in the details,” said Wes LeBlanc, a way director and capital at Gensler.

Post Comment