What is rage-baiting and why is it profitable?

What is rage-baiting and why is it profitable?

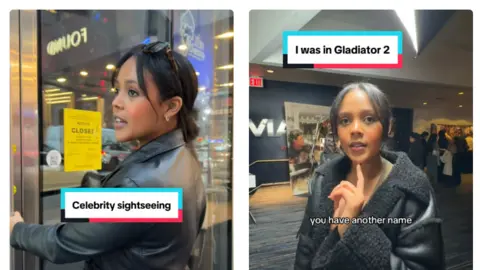

Winta Zesu

Winta Zesu“I get a lot of despise”. The words of content creator Winta Zesu, who last year made $150,000 (£117,000) from posting on social media.

What separates Winta from other influencers? The people commenting on her posts and driving traffic to her videos are often doing so out of rage.

“Every single video of mine that has gained millions of views is because of despise comments,” the 24-year-ancient explains.

In those videos, she documents the life of a recent York City model, whose biggest issue is being too pretty. What some in the comments don’t realise, is that Winta is playing a character.

“I get a lot of nasty comments, people declare ‘you’re not the prettiest girl’ or ‘please bring yourself down, you have too much confidence’,” she says to the BBC from her recent York City apartment.

Winta is part of a growing throng of online creators making ‘rage bait’ content, where the objective is straightforward: record videos, produce memes and write posts that make other users viscerally angry, then bask in the thousands, or even millions, of shares and likes.

It differs from its internet-cousin clickbait, where a headline is used to tempt a reader to click through to view a video or piece.

As marketing podcaster Andrea Jones notes: “A hook reflects what’s in that piece of content and comes from a place of depend, whereas rage-baiting content is designed to be manipulative.”

But the grip negative content has on human psychology is something that is hardwired into us, according to Dr William Brady, who studies how the brain interacts with recent technologies.

“In our history, this is the benevolent of content that we really needed to pay attention to,” he explains, “so we have these biases built into our learning and our attention.”

Megan Muir

Megan MuirThe growth in rage baiting content has coincided with the major social media platforms paying creators more for their content.

These creator programs – which reward users for likes, comments and shares, and allow them to post sponsored content – have been linked to its rise.

“If we view a cat, we’re like ‘oh, that’s cute’ and scroll on. But if we view someone doing something obscene, we may type in the comments ‘this is terrible’, and that sort of comment is seen as a higher standard engagement by the algorithm,” explains marketing podcaster Andréa Jones.

“The more content a user creates the more engagement they get, the more that they get paid.

“And so, some creators will do anything to get more views, even if it is negative or inciting rage and rage in people,” she says with a note of concern. “It leads to disengagement.”

Rage bait content comes in many forms, from outrageous food recipes, to attacks on your favourite popstar. But in a year of global elections, particularly in the US, rage baiting has spread to politics too.

As Dr Brady observes: “There has been a spike in the construct up to elections, because it’s an effective way to mobilize your political throng to potentially vote and receive action.”

He notes the American election was light on policy, and instead centred around outrage, adding, “it was hyper-concentrated on ‘Trump is horrible for this rationale’ or ‘Harris is horrible for that rationale’.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAn investigation from BBC social media investigations correspondent Marianna Spring found some users on X were being paid “thousands of dollars” by the social media site, for sharing content including misinformation, AI-generated images and unfounded conspiracy theories.

Some who study the trends are concerned that too much negative content can navigator to the average person “switching off”.

“It can be draining to have such high emotions all the period,” says Ariel Hazel, assistant professor of communication and media at the University of Michigan.

“It turns them off the information surroundings and we’re seeing increased amounts of energetic information avoidance around the globe.”

Others worry about normalising rage offline and the eroding effects on people’s depend in the content they view.

“Algorithms amplify outrage, it makes people ponder it’s more normal,” says social psychologist Dr William Brady.

He adds: “What we recognize from sure platforms like X is that politically extreme content is actually produced by a very tiny fraction of the user base, but algorithms can amplify it as if they were more of a majority.”

The BBC contacted the main social media platforms about rage bait on their sites, but had no responses.

In October 2024, Meta executive Adam Mosseri posted on Threads about “an boost in engagement-bait” on the platform, adding, “we’re working to get it under control.”

While Elon Musk’s rival platform X, recently announced a transformation to its Creator income Sharing Program which will view creators compensated based on engagement from the site’s additional expense users – such as likes, replies, and reposts. Previously compensation was based on ads viewed by additional expense users.

TikTok and YouTube allow users to make money from their posts or to distribute sponsored content too, but have rules which allow them to de-monetise or suspend profiles that post misinformation. X does not have guidelines on misinformation in the same way.

Back in Winta Zesu’s recent York City apartment, the exchange – which is taking place days before the US election – turns to politics.

“Yeah, I don’t consent with people using rage bait for political reasons,” the content creator says.

“If they’re using it genuinely to educate and inform people, it’s fine. But if they’re using it to spread misinformation, I totally do not consent with that.

“It’s not a joke anymore.”

Post Comment