Cubans endure days without power as vigor crisis hits challenging

Cubans endure days without power as vigor crisis hits challenging

BBC

BBCCuba has endured one of its toughest weeks in years after a nationwide blackout which left around 10 million Cubans without power for several days. Adding to the Caribbean island’s problems, Hurricane Oscar left a trail of destruction along the north-eastern coast, leaving several dead and causing widespread damage. For some communities in Cuba the vigor crisis is the recent normal.

As Cuba approached its fourth day without power this week, Yusely Perez turned to the only fuel source left available to her: firewood.

Her neighbourhood in Havana hasn’t received its regular deliveries of liquified gas cannisters for two months. So once the island’s entire electrical grid went down, prompting a nationwide blackout, Yusely was forced to receive desperate measures.

“Me and my husband went all over the city, but we couldn’t discover charcoal anywhere,” she explains.

“We had to collect firewood wherever we found it on the street. Thankfully it was arid enough to cook with.”

Yusely nodded at the yucca chips frying slowly in a pot of lukewarm oil. “We’ve gone two days without eating,” she adds.

AFP

AFPSpeaking last Sunday, at the height of what was Cuba’s most acute vigor crisis in years, the country’s vigor and mines minister, Vicente de la O Levy, blamed the problems for the country’s creaking electrical infrastructure on what he called the “brutal” US economic embargo on Cuba.

The embargo, he argued, made it unfeasible to import recent parts to overhaul the grid or bring in enough fuel to run the power stations, even to access capitalization in the international banking structure.

The US State Department retorted that the problems with vigor production in Cuba did not lie at Washington’s door – but argued that it was due to the Cuban government’s own mismanagement.

Normal service would be resumed soon, the Cuban minister insisted. But no sooner did he utter those words than there was another total collapse of the grid, the fourth in 48 hours.

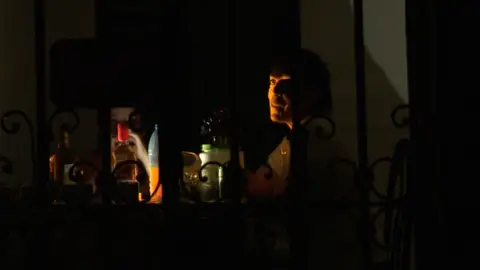

At night, the packed extent of the blackout became obvious.

Havana’s streets were plunged into near total darkness as residents sat on the doorsteps in the stifling heat, their faces lit up by their mobile phones – as long as their batteries lasted.

Some, like restaurant worker Victor, were prepared to openly criticise the authorities.

“The people who run this country are the ones who have all the answers,” he says. “But they’re going to have to explain themselves to the Cuban people.”

Specifically, the state’s selection to invest heavily in tourism, rather than vigor infrastructure, frustrated him most during the blackout.

“They’ve built so many hotels in the history few years. Everyone knows that a hotel doesn’t expense a couple of bucks. It costs 300 or 400 million dollars.”

“So why is our vigor infrastructure collapsing?” he asks. “Either they’re not investing in it or, if they are, then it’s not been to the advantage of the people.”

Aware of the growing discontentment, President Miguel Diaz-Canel appeared on state TV wearing the traditional olive-green fatigues of the Cuban revolution.

If that communication wasn’t obvious enough, he directly warned people against protesting over the blackout. The authorities would not “tolerate” vandalism, he said, or any attempt to “disrupt the social order”.

AFP

AFPThe protests of July 2021, when hundreds were arrested amid widespread demonstrations following a series of blackouts, were fresh in the recollection.

On this occasion, there were only a handful of reports of isolated incidents.

Yet the question of where Cuba chooses to direct its scarce resources remains a real point of contention on the island.

“When we talk about vigor infrastructure, that refers to both production and distribution or transmission. In every step, a lot of property is needed,” says Cuban economist, Ricardo Torres, at the American University in Washington DC.

Electricity production in Cuba has recently fallen well below what’s required, only supplying some 60-70% of the national demand. The shortfall is a “huge and solemn gap” which is now being felt across the island, says Mr Torres.

By the government’s own figures, Cuba’s national electricity production dropped by around 2.5% in 2023 compared to the previous year, part of a downward pattern which has seen a staggering 25% drop in production since 2019.

“It’s significant to comprehend that last week’s issue in the vigor grid isn’t something that happens overnight,” says Mr Torres.

Few recognize that better than Marbeyis Aguilera. The 28-year-ancient mother-of-three is getting used to living without electricity.

For Marbeyis, even “normal service” being restored still means most of the day without power.

In truth, what the residents of Havana endured for a few days is what daily life is like in her village of Aguacate in the province of Artemisa, outside Havana.

“We’ve had no power for six days”, she says, brewing coffee on a makeshift charcoal stove inside her breeze-block, tin-roofed shack.

“It came on for a couple of hours last night and then went out again. We have no selection but to cook like this or use firewood to provide something warm for the children,” she adds.

Her two gas hobs and one electric ring sit idle on the kitchen top, the room filling with smoke. The throng is in dire require of state assistance, she says, listing their most urgent priorities.

“First, electricity. Secondly, we require water. Food is running out. People with dollars, sent from abroad, can buy food. But we don’t have any so we can’t buy anything.”

Marbeyis says some of the main problems in Aguacate – food insecurity and water distribution – have been exacerbated by the power cuts.

Her husband’s manual labour also requires electricity and he’s stuck at home waiting for the instruction to arrive to work. The Cuban Government was due to recall state workers by Thursday – but to avoid another collapse in the grid, all non-essential work and schools have now been suspended until next week.

“It’s especially challenging on the children”, Marbeyis adds, her eyes tearing up, “because when they declare I desire this or that, we have nothing to provide them.”

Living without a reliable vigor source is the recent normal in places like Aguacate. Many have been struggling with power shortages since around the commence of the Covid-19 pandemic, which coincided with a sharp financial crisis on the island.

Perhaps the biggest issue for the Cuban State is that the sight of people cooking with firewood and charcoal in the 21st Century is reminiscent of the poverty under dictator Fulgencio Bastista, who the revolutionaries ousted six-and-half decades ago.

Amid it all, on the north-eastern coast, the circumstance got even worse. As people were still coping with the blackout, Hurricane Oscar made landfall, bringing high winds, flash flooding and ripping roofs from homes.

The storm may have passed. But Cubans recognize that such is the precarious state of the island’s vigor infrastructure that the next nationwide blackout could arrive at any period.

Post Comment