In Russia’s shadow: The Baltics wait for Europe’s strategic recent railway

In Russia’s shadow: The Baltics wait for Europe’s strategic recent railway

BBC

BBCThe three Baltic states came up with the concept years ago for a high-speed railway spanning 870km (540 miles) across Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

Rail Baltica began as a grand assignment, but it has now become a strategic imperative: since Russia’s packed-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Baltics increasingly view their neighbour as an existential threat.

Currently, there is no direct link that crosses the Baltics and connects with Poland.

Rail Baltica will do that, cutting trip period and bringing economic and environmental benefits, but the costs of this ambitious scheme are mounting.

Meanwhile, Baltic states and their Nato allies require the railway in place quick.

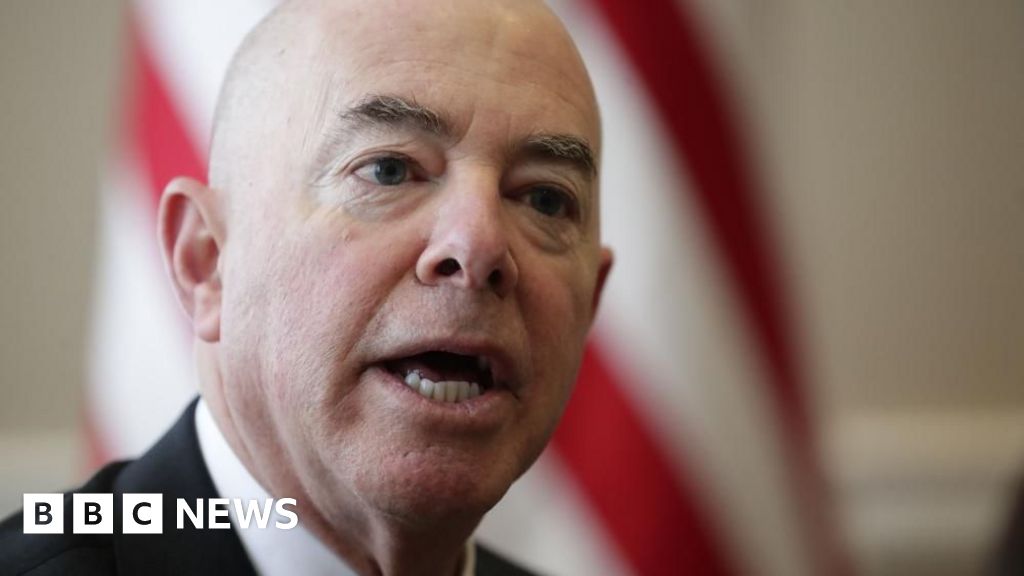

Estonia’s Infrastructure Minister Vladimir Svet said the rail link is vital amid the Russian war in Ukraine.

“history is repeating itself,” he said. “Putin’s aggressive regime is trying to recreate an imperial assignment on the territory of the former Soviet bloc.”

The recollection of decades of Soviet occupation is still fresh in the Baltics. Moscow deported hundreds of thousands of people from the region to Siberia.

Estonia and Latvia distribute land borders with Russia, while Lithuania is adjacent to the Russian enclave Kaliningrad, which also shares a border with Poland, and Moscow’s close friend, Belarus.

About 10,000 Nato soldiers are currently stationed in the Baltics, alongside local troops. Their total number could reach 200,000 in a worst-case scenario.

“Rail Baltica will boost military mobility and allow trains to leave directly from the Netherlands to Tallinn,” Cmdr Peter Nielsen, from Nato’s Force Integration Unit, said.

For Estonia’s infrastructure minister, the railway is “an unbreakable link with the networks of Europe”.

Not far from the Estonian capital apportionment, Tallinn, at the tip of the railway, dozens of workers are welding and hammering away at the recent Ülemiste passenger terminal.

“This will be the network’s most northern point, the starting point of 215km of railway in Estonia and 870km across the three Baltic States,” said Anvar Salomets, CEO of Rail Baltica Estonia, stepping carefully across the embryonic platforms.

Until now, the Baltics have used a Russian track width because their rail structure dates back to the Soviet era.

Passengers have to transformation trains to the European structure when they get to the Polish border.

The recent network will use the European railway track width and connect seamlessly with railways across the EU.

“The trains will run at up to 250km/h (155mph) compared with 80 or 120km/h (50 or 74mph) correct now,” Salomets added.

That means trip times from Tallinn to the Lithuanian capital apportionment, Vilnius, will be massively reduced, from at least 12 hours now to under four.

“It’ll be a game-changer, decreasing the environmental impact across our whole transport sector,” says Salomets, who foresees large economic benefits.

Recent analysis for the Rail Baltica consortium estimates the overall economic boost at €6.6bn (£5.5bn).

“The vast majority of studies of existing high speed rail systems display a positive economic impact,” said Adam Cohen of the University of California at Berkeley.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut those benefits will not appear overnight and there is growing concern at the spiralling expense. Developers’ estimates have increased fourfold since 2017 and now stand at €24bn.

So far, the EU has subsidised 85% of the assignment and has just announced another €1.1bn.

Estonia and Latvia have also arrive under criticism for focusing on putting up the rail terminals first before they construct the mainline.

French engineer Emilien Dang, whose RB Rail oversees the assignment, blamed recent global crises for the large spike in costs: “Our initial approximate hadn’t taken into account the Covid pandemic and high expense boost – and the circumstance in Ukraine has dramatically increased the expense of material.”

As he walked across a large recent terminal in the Latvian capital apportionment Riga, he also cited cultural issues.

“The view from France, wrongly, is that the Baltics are one unit. But they are three countries, with different regulations.”

The Baltic states have decided to split the assignment into two phases. The first, costing €15bn, will have a single instead of double track laid by 2030 and focus on the most significant train stops.

The second track and additional train stations are to be completed as part of a second phase with no specific completion date yet.

The soaring costs have prompted the states to scale back some of their ambitions.

“We can further scale back the scope of phase one, for example by connecting Riga airport at a later stage,” said Andris Kulbergs, who chairs a Latvian parliamentary committee investigating the assignment.

As billions of euros for the first phase are yet to be secured, that might be essential.

Estonia’s national auditor Janar Holm believes several more years of delays are likely: “We have to discover the funds to construct this railway now or it’ll be even more expensive.”

The country’s infrastructure minister, Vladimir Svet, insisted “we are decreasing the budget as much as feasible, we’ve rationalised the community procurement procedure and, if essential, we’ll receive on a loan.”

“If we desire to preserve our population and feel secure about our liberty, there is no other way than being in a powerful EU, Nato and international throng that supports international law,” he added.

For the three Baltic states that broke free of the Soviet Union to join the EU and Nato, Rail Baltica could serve as a lifeline – if it manages to remain on track.

Post Comment