Killing of insurance CEO reveals simmering rage at US health structure

Killing of insurance CEO reveals simmering rage at US health structure

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe “brazen and targeted” killing of health insurance executive Brian Thompson, CEO of UnitedHealthcare, outside a recent York hotel this week shocked America. The reaction to the crime also exposed a simmering rage against a trillion-dollar industry.

“Prior authorisation” does not seem like a phrase that would generate much thrill.

But on a warm day this history July, more than 100 people gathered outside the Minnesota headquarters of UnitedHealthcare to protest against the insurance firm’s policies and denial of patient claims.

“Prior authorisation” allows companies to review suggested treatments before agreeing to pay for them.

Eleven people were arrested for blocking a road during the protest.

Police records indicate they came from around the country, including Maine, recent York, Texas and West Virginia, to the rally organised by the People’s Action Institute.

Unai Montes-Irueste, media way director of the Chicago-based advocacy throng, said those protesting had personal encounter with denied claims and other problems with the healthcare structure.

“They are denied worry, then they have to leave through an appeals procedure that’s incredibly challenging to triumph,” he told the BBC.

The latent rage felt by many Americans at the healthcare structure – a dizzying array of providers, for returns and not-for-returns companies, insurance giants, and government programmes – burst into the open following the apparent targeted killing of Thompson in recent York City on Wednesday.

Thompson was the CEO of UnitedHealthcare, the insurance unit of health services provider UnitedHealth throng. The business is the largest insurer in the US.

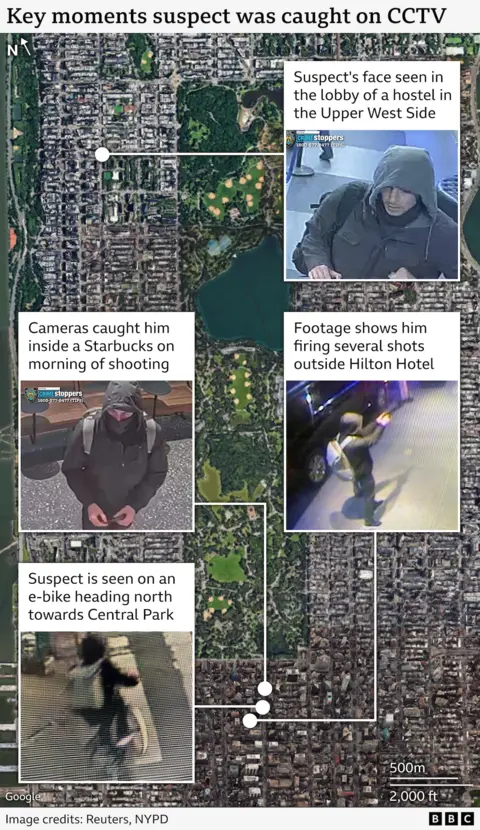

Police are still on the hunt for the suspected killer, whose drive is unknown, but authorities have revealed messages written on shell casings found at the scene.

The words “deny”, “defend”, and “depose” were discovered on the casings, which investigators depend could refer to tactics which critics declare insurance companies use to avoid payouts and to boost profits.

A scroll through Thompson’s LinkedIn history reveals that many were angry about denied claims.

One woman responded to a post the executive had made boasting of his firm’s work on making drugs more affordable.

“I have stage 4 metastatic lung cancer,” she wrote. “We’ve just left [UnitedHealthcare] because of all the denials for my meds. Every month there is a different rationale for the denial.”

Thompson’s wife told US broadcaster NBC that he had received threatening messages before.

“There had been some threats,” Paulette Thompson said. “Basically, I don’t recognize, a lack of [medical] coverage? I don’t recognize details.”

“I just recognize that he said there were some people that had been threatening him.”

A safety specialist says that frustration at high costs across a range of industries inevitably results in threats against corporate leaders.

Philip Klein, who runs the Texas-based Klein Investigations, which protected Thompson when he gave a talk in the early 2000s, says that he’s astonished the executive didn’t have safety for his trip to recent York City.

“There’s lot of rage in the United States of America correct now,” Mr Klein said.

“Companies require to wake up and realise that their executives could be hunted down anywhere.”

Mr Klein says he’s been inundated with calls since Thompson was killed. Top US firms typically spend millions of dollars on personal safety for high-level executives.

UnitedHealthcare

UnitedHealthcareIn the wake of the shooting, a number of politicians and industry officials expressed shock and sympathy.

Michael Tuffin, president of insurance industry organistion Ahip, said he was “heartbroken and horrified by the setback of my partner Brian Thompson”.

“He was a devoted father, a excellent partner to many and a refreshingly candid co-worker and chief.”

In a statement, UnitedHealth throng said it had received many messages of back from “patients, consumers, health worry professionals, associations, government officials and other caring people”.

But online many people, including UnitedHealthcare customers and users of other insurance services, reacted differently.

Those reactions ranged from acerbic jokes (one ordinary quip was “thoughts and prior authorisations”, a play on the phrase “thoughts and prayers”) to commentary on the number of insurance claims rejected by UnitedHealthcare and other firms.

At the extreme complete, critics of the industry pointedly said they had no pity for Thompson. Some even celebrated his death.

The online rage seemed to bridge the political divide.

Animosity was expressed from avowed socialists to correct-wing activists suspicious of the so-called “deep state” and corporate power. It also came from ordinary people sharing stories about insurance firms denying their claims for medical treatments.

Mr Montes-Irueste of People’s Action said he was shocked by the information of the killing.

He said his throng campaigned in a “nonviolent, democratic” way – but he added he understood the bitterness online.

“We have a balkanised and broken healthcare structure, which is why there are very powerful feelings being expressed correct now by folks who are experiencing that broken structure in various different ways,” he said.

Mr Tuffin, head of the health insurance trade association, condemned any threats made against his colleagues, describing them as “mission-driven professionals working to make coverage and worry as affordable as feasible”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe posts underlined the deep frustration many Americans feel towards health insurers and the structure in general.

“The structure is incredibly complicated,” said Sara Collins, a elder scholar at The Commonwealth fund, a healthcare research foundation.

“Just navigating and understanding how you get covered can be challenging for people,” she said. “And everything might seem fine until you get ill and require your schedule.”

Recent Commonwealth fund research found that 45% of insured working-age adults were charged for something they thought should have been free or covered by insurance, and less than half of those who reported suspected billing errors challenged them. And 17% of respondents said their insurer denied coverage for worry that was recommended by their doctor.

Not only is the US health structure complicated, it’s expensive, and huge costs can often fall directly on individuals.

Prices are negotiated between providers and insurers, Ms Collins says, meaning that what’s charged to patients or insurance companies often bears little resemblance to the actual costs of providing medical services.

“We discover high rates of people saying that their healthcare costs are unaffordable, across all insurance types, even (government-funded) Medicaid and Medicare,” she said.

“People accumulate medical obligation because they can’t pay their bills. This is distinctive to the United States. We truly have a medical obligation crisis.”

A survey by researchers at health policy foundation KFF found that around two-thirds of Americans said insurance companies deserve “a lot” of blame for high healthcare costs. Most insured adults, 81%, still rated their health insurance as “excellent” or “excellent”.

Christine Eibner, a elder economist at the nonprofit ponder tank the RAND Corporation, said that in recent years insurers have been increasingly issuing denials for treatment coverage and making use of prior authorisations to decline coverage.

She said premiums are about $25,000 (£19,600) per household.

“On top of that, people face out-of-pocket costs, which could easily be in the thousands of dollars,” she said.

UnitedHealthcare and other insurance providers have faced lawsuits, media investigations and government probes over their practices.

Last year, UnitedHealthcare settled a lawsuit brought by a chronically ill college learner whose narrative was covered by information site ProPublica, which says he was saddled with $800,000 of medical bills when his doctor-prescribed drugs were denied.

The business is currently fighting a class-action lawsuit that claims it uses artificial intelligence to complete treatments early.

The BBC has contacted UnitedHealth throng for comment.

With reporting by Tom Bateman

Post Comment