London’s disappeared department stores of days gone by

London’s disappeared department stores of days gone by

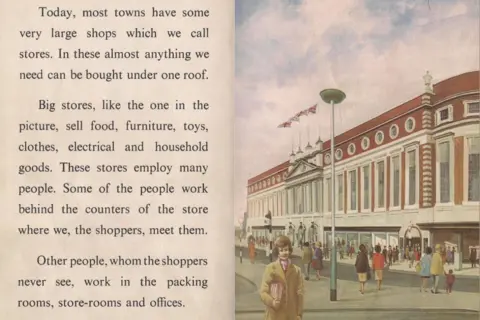

Once the bastion of middle-class ladies going up to town to shop, with deferential and attentive staff and a respectable place to lunch, department stores were a globe away from today’s shopping habits of e-commerce, quick fashion and middle aisles filled with snorkels, ladders and tapestry kits.

In the early 1900s, London had more than 100 – each offering a huge range of goods.

Here are just some of the pool’s behemoths of the period, now gone from the streets and all but gone from the recollection.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBourne & Hollingsworth, 1894-1983

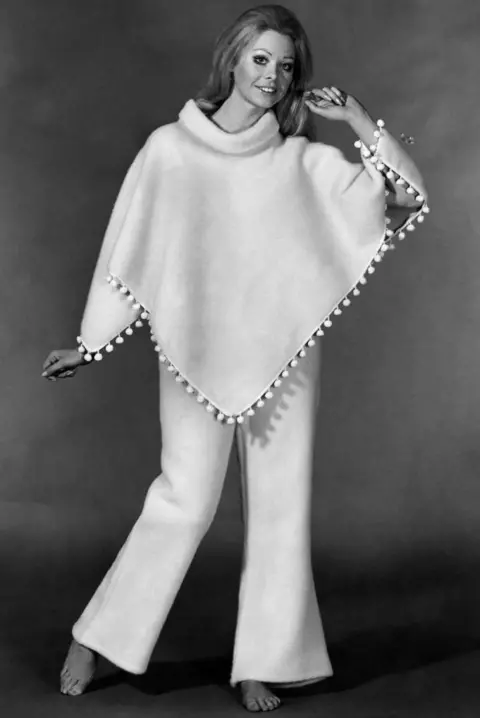

If in 1969 one wanted to “leave gay Mexican” as one advert put it, a remarkable garment called “poncho pyjamas” became available at Bourne & Hollingsworth on Oxford Street.

The promotion continued: “overlook about sleeping in them. These are for girls who are wide awake to the trendiest fashions. Wear them for lazy evenings at home – or get-up-and-leave to a event in them.”

The brushed acrylic outfit, with a cowl neckline, flared trousers and bobble trim, was available in pink, blue, royal, green, red or white and retailed for £6 12s. 6d.

In today’s money, allowing for expense boost, that’s just over £100.

Bourne & Hollingsworth also had a staff hostel for unmarried females on Gower Street, where presumably shop wages were insufficient to clad every resident in poncho pyjamas, no matter how much they wanted to leave gay Mexican.

Getty Images

Getty Images Getty Images

Getty ImagesOne hostel resident remembered: “I first worked in the ladies’ suit department and recall selling a suit to the actress Billie Whitelaw.

“When a client entered the department, the buyer would declare ‘forward 596’ – we were given numbers instead of being called by our name.

“I loved my period there and frequently swam in the pool in the basement, and played table tennis in the ballroom.”

IWM via Getty

IWM via Getty Getty Images

Getty ImagesGamages 1878-1972

In 1878, 21-year-ancient Albert Gamage decided to use his funds of £40 (about £4,000 today) to open his own shop.

He and another man, Frank Spain, clubbed together and leased a tiny premises in Holborn.

The frugal pair lived in a back room and allowed themselves a maximum of 14 shillings a week for all costs.

Mr Gamage bought out Mr Spain in 1881, and began to buy other tiny properties around his shop to expand the business.

By 1890, most of the block between Leather Lane and Hatton Garden was his.

Getty Images

Getty Images Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis piecemeal way of purchase led to the ever-growing emporium becoming a maze of ramps, passages and rooms, adding an element of expedition for customers as they wandered in search of bargains.

A zoo department and a toy department were joined by a motor department selling cars, motorbikes and all associated accoutrements.

Their mail-order catalogues became famous for their offerings of toys and bicycles in particular.

Gamages also became the official supplier of Cub Scout uniforms.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOne promotion in 1936 saw an elephant named Mae West co-opted to promote the Christmas bazaar.

She was photographed accepting an apple from a passing tram driver while ambling along Gray’s Inn Road.

The image had an fascinating upcoming – it was often circulated with the untrue narrative that the notorious Kray twins used a stolen elephant to extort protection from tram drivers.

Commons

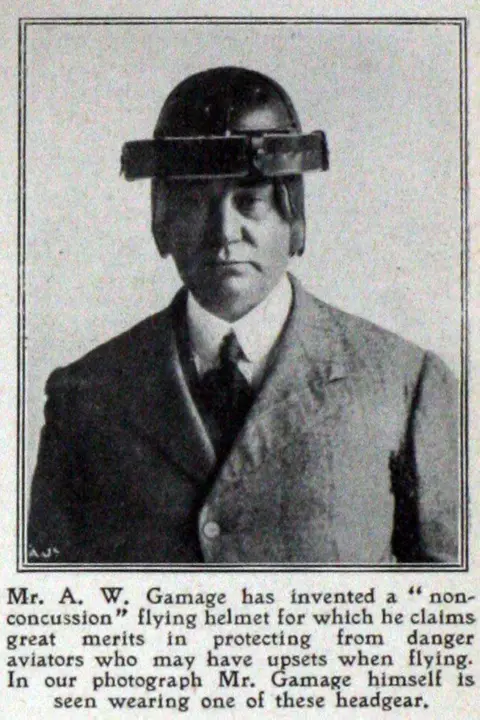

CommonsIn 1910 it was announced Mr Gamage had “invented a non-concussion flying helmet” to protect aviators.

He died in 1930, without being concussed in the field of aviation, aged 74. He and his wife Jane had three sons and a daughter, lived in a manor house, and had nine servants.

The Holborn premises closed in March 1972 and disappeared in a massive redevelopment scheme.

John Lewis archive

John Lewis archivePratts c.1845-1990

Captain Darling, Blackadder’s nemesis in the final series, worked at Pratts before globe War One.

In one poignant scene, he said: “Rather hoped I’d get through the whole display.

“leave back to work at Pratt and Sons, keep wicket for the Croydon Gentlemen, marry Doris…”

Pratt’s narrative began in 1840 when 13-year-ancient George Pratt started a drapery apprenticeship in Streatham Village. About five years later he bought the shop.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOnly a tiny part of the building went above ground floor level, resulting in selling space on the lower-ground and ground floors only.

Eventually, departments were moved out of the main building. Soft furnishings went across the street, the dress department was moved further up the road, and warehousing was developed at two more locations.

The store was bought by Brixton rival Bon Marché in 1919, which in turn was bought by Selfridges in 1926.

And then in 1940, the John Lewis collaboration bought it all.

Pratts archive

Pratts archive

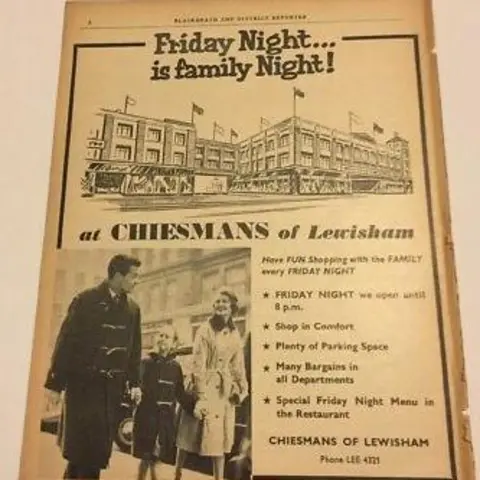

Chiesmans 1884-1976

Two brothers, Frank and Harry Chiesman, opened a drapery shop in Lewisham in 1884.

The business became involved in recruiting for the war attempt in 1914, even erecting a tent as a place for men to sign up to the local regiment.

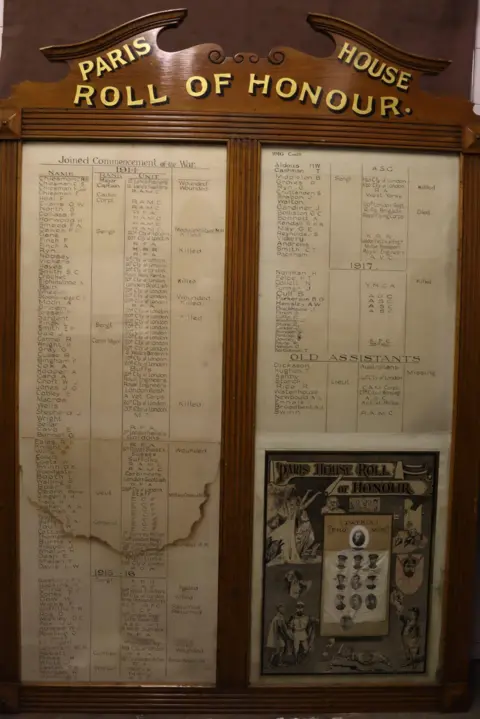

Men who served were written on an honour roll displayed at the store’s original premises, Paris House.

Lewisham archives

Lewisham archivesThe importance of the firm to previous employees was demonstrated when information of their exploits were printed in the local press, as the source was often other former employees.

Lewisham Borough information had updates gleaned from letters sent to Chiesmans.

In August 1915, FG Dawe wrote: “I sincerely aspiration one or the other of the boys have kept you informed of our well-being.”

He mentions a co-worker, “Pte McCrow has just recently joined us, so the firm is well represented.”

He asked after ex-Chiesmans men serving elsewhere, refers to having seen a postcard of the roll of honour and asks the firm to send him a copy.

Macrow is listed on the honour roll as having joined up in 1914. He was killed in action in December 1915.

And the correspondent, FG Dawe, was killed at the Battle of Loos, just a month after writing his note.

Lewisham archive

Lewisham archiveStuart Chiesman, son of Frank, was wounded in the foot on the Somme in 1916 and medically discharged from the Army.

He was recovering in Brighton when – as recounted by the Blackheath Advertiser in July 1917 – he made a daring rescue of an eight-year-ancient girl.

“He threw down his crutches, tore off his tunic, and dived from the top of the pier.

“He brought the little girl, who was unconscious and in a solemn state of collapse, to safety, although the wounded left leg – heavily bandaged – hung like a log in the water, the wound suppurating.

“Whilst he was engaged in rescuing the kid, his gold watch and £5, left in his tunic pockets, were stolen.”

Ladybird

LadybirdWhiteleys, 1863-1981

Unlike the household mood nurtured by the Chiesman brothers, William Whiteley had a challenging head for business.

In 1848 he apprenticed to a large drapery in Wakefield, and after a visit to the Great demonstration at Crystal Palace he set his ambitions on establishing his own vast emporium.

By 1863 he had enough money to set up in Westbourne Grove and by 1875 he had an unbroken row of shops.

But he was not well liked.

Smaller businesses were annoyed he was taking their customers – he offered such a range of products at low prices that in 1876 a throng of Bayswater tradesmen burned his effigy on Guy Fawkes Night.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhiteleys was set fire to a number of times.

In 1887 the recent York Times ran an piece called The Burning of Whiteley’s Great Establishment: “The setback is estimated at $2,500,000 – incendiarism is suspected.”

The Times newspaper said: “The outbreak could not be subdued until three large buildings, each of five floors, had been completely gutted, and three others very seriously damaged by fire, heat, and water.

“It was quickly seen by the firemen that the fire threatened to prove of as destructive a character as the three which have preceded it on the same spot in the last three years.”

John Fraser archive

John Fraser archive Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn 24 January 1907, William Whiteley was shot dead.

A youthful man claiming to be his illegitimate son, Cecil Whiteley, had confronted him in his office, and tried to blackmail him.

On being sent away with a flea in his ear, “Cecil” shot Mr Whiteley and then himself.

Mr Whiteley died – Cecil, who was actually called Horace Rayner, did not.

Rayner had convinced himself of the household connection because his father and Mr Whiteley had both been “amiable” with a pair of sisters and would visit them together.

There was a quarrel, and the two men fell out, never to be friends again. One of the sisters was Rayner’s mother.

Rayner was later convicted of murder and sentenced to death, commuted to a life term.

He was freed from prison after serving 11 years.

Getty Images

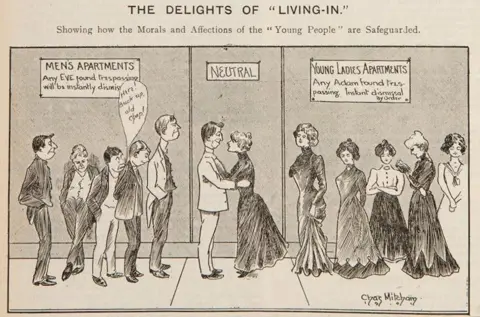

Getty ImagesAccording to heritage body Historic England, there was no luxury for the working-class women and girls Whiteleys “exploited” as shop assistants.

Assistants had to stand all day, and were expected to work six days a week from 07:00 until 23:00.

They were forced to live at the shop, dine in the staff cafeteria – and pay for the impoverished-standard food provided.

A note from a member to the Shop Assistants’ Union testified: “The bedrooms are like barns, with water trickling down the walls…and we cannot sleep for the cold.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWorkers were not allowed to leave out, and could be fined for “gossiping and idleness”.

In May 1880, the Kilburn Times reported a London shop girl had “drowned herself, the act being attributed to excessive pain from standing for so many hours in the shop”.

The Pall Mall Gazette suggested in December 1887 that employers could “provide reasonable comfort consistent with the business interests of the establishment,” such as an afternoon a week off, and permission to sit down when it did not interfere with the job.

Such tiny comforts, though, did not transpire.

Following his death, Mr Whiteley’s two sons carried on operating the business, eventually selling to Gordon Selfridge in 1927.

Union of Shop, Distributive and Allied Workers

Union of Shop, Distributive and Allied WorkersMarshall & Snelgrove 1837-1974

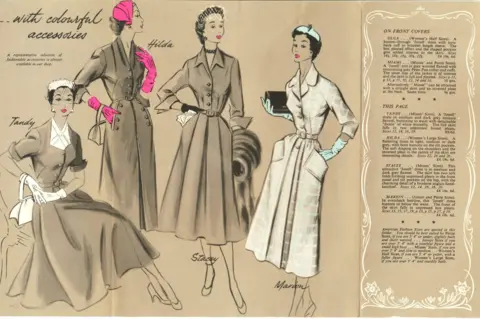

Another grand establishment on Oxford Street, Marshall & Snelgrove had an air of exclusivity cultivated by maintaining an on-site couturier workroom to supplement the ready-to-wear lines.

A position as an apprentice in the store was so prestigious it could only be secured with a investment of 60 guineas.

It even opened branches in fashionable resorts such as Scarborough and Harrogate to enable their customers to shop while on holiday.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe privations of globe War One forced it, as a luxury brand, into collaboration with Debenhams.

The arrangement carried on until 1919, when a packed union was made – although the Oxford Street store continued to trade under the Marshall & Snelgrove name.

In 1974 the building was renovated and the name was changed to Debenhams.

Getty Images

Getty Images Getty Images

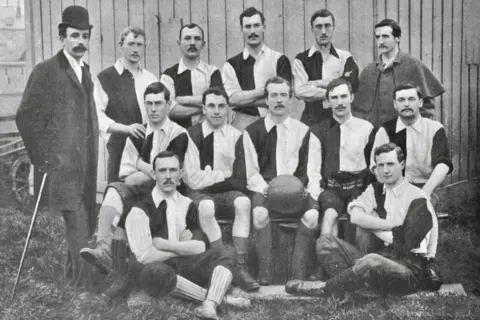

Getty ImagesOne of the extracurricular successes of Marshall & Snelgrove was its football throng.

Competing as West complete, the throng’s first recorded match was in October 1873, and in the 1879-80 period it reached the fourth round (last 10) of the FA Cup.

(This achievement might be tempered with the knowledge the throng benefited from one bye, and one walkover when another throng withdrew.)

Illustrated London information

Illustrated London informationIn the West complete test Cup – a more modest endeavour set up in 1881 for works sides from “large retail houses” they beat the Prairie Rangers (Harvey Nichols) 3–0 in the final in front of a throng of 1,500.

The write-up included the memorable line “Foster scored twice – the second by breasting home a corner”.

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and pursue BBC London on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your narrative ideas to [email protected]

Post Comment