The water industry is in crisis. Can it be fixed?

The water industry is in crisis. Can it be fixed?

BBC

BBCOur loos flush and water comes out of our taps. In that sense, the water industry in England and Wales works. In just about every other way, it’s a mess.

The most visible sign of that mess comes after those loos have flushed. Last year England’s privatised water firms released raw sewage for a total of 3.6m hours, more than double the amount recorded the year before.

Millions of customers, surfers and bathers have joined a chorus that former pop star Feargal Sharkey has been singing for years – that the sector is a “disordered shambles”.

It’s not just our rivers, lakes and coastlines. Some communities have been told to boil tap water to make it secure, others have seen their water supplies cut off for days or even weeks.

surroundings Secretary Steve Reed told the BBC some parts of the country could face a drinking water shortage by the 2030s and plans to construct recent homes have been jeopardised by water supply problems.

belief in these companies has never been lower and it’s not challenging to view why.

There are some ordinary denominators causing stress on the structure that will receive radical reform to tackle. The government knows this – which is why it has just announced a major recent percentage to conduct the biggest review of the sector since privatisation 35 years ago.

The independent percentage will be led by former lender of England Deputy Governor Sir Jon Cunliffe and will update back with recommendations next June. Options on the table include the reform or abolition of the main regulator Ofwat.

To critics like Sharkey, the former navigator singer of the Undertones who nowadays is vocal about the state of UK’s rivers, it’s an admission that the privatisation of essential monopolies has been a setback. Recently, he described this as “possibly the greatest organised ripoff perpetrated on the British people”.

So how did we get here, how might it be fixed and what will that cruel for customers and their bills?

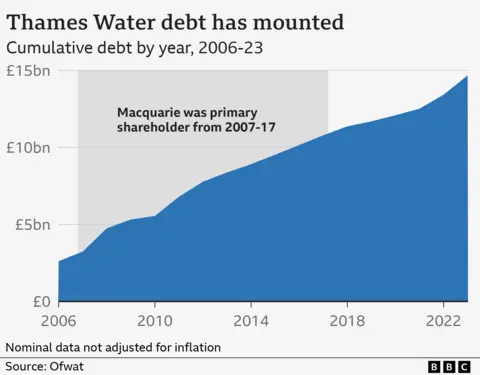

Drowning in debt

Reflecting on water privatisation in her memoirs, Margaret Thatcher wrote that “the rain may arrive from the Almighty but he did not send the pipes, plumbing and engineering to leave with it”.

When her government privatised the water companies in the late 1980s, they were debt free. Today they have a combined £60bn in debt.

There is nothing intrinsically incorrect with debt. It can be a expense-efficient way to finance property in an industry that lenders have been very joyful to lend to.

And it’s straightforward to view why they’ve been so joyful to lend to it. Water companies have guaranteed and rising income from customers, who can’t leave anywhere else for something they will always require. Regional monopolies of an essential service that provides a guaranteed income have always been considered a secure bet.

The other attraction for shareholders in water companies, like others, is that the expense of the borrowing repayments can be deducted from profits to reduce reported boost and therefore their levy invoice.

Some shareholders, not all, have pushed this too far and loaded an excessive amount of debt on water companies. That can backfire when the expense of that debt begins to rise – as we have seen over the last two years as earnings rates rose to tackle the surge in expense boost since 2022.

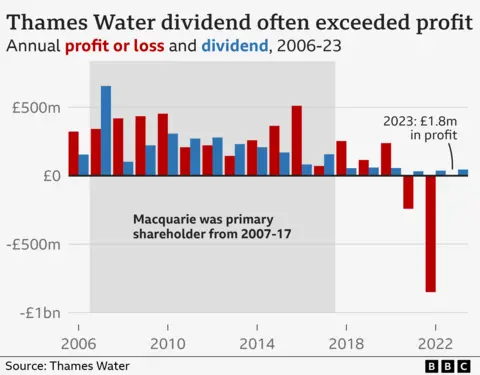

For example, during the 10 years that Australian property firm Macquarie was Thames Water’s biggest shareholder from 2007 to 2017, debt rose from £2bn to £11bn, during which period Macquarie and the other investors did not inject any recent liquid assets or ownership of their own.

In five years out of the 10 that Macquarie was a major shareholder in Thames Water, investors took out more money in dividends than the corporation made in boost and made up the shortfall by borrowing heavily while letting debt levels soar.

Thames Water now stands on the brink of insolvency with barely enough liquid assets to last until the complete of the year.

Macquarie sold its distribute of the corporation in 2017. Newer shareholders, including large domestic and foreign superannuation funds, recently cancelled an injection of £500m. They did so after they learned that Ofwat would not allow invoice rises that the newer shareholders insisted were essential if their property was to earn a profit for their own pensioners and shareholders.

In a statement, a spokesperson for Macquarie said: “We supported Thames Water as it delivered record levels of property, which enabled the corporation to reduce leakage and pollution incidents while improving drinking water standard and safety of supply. Much more needed to be done to upgrade its legacy infrastructure, but when we sold our final stake in 2017 the corporation was conference all conditions set by the regulator and had an property grade financing rating.”

Thames Water’s debt today stands at over £16bn and the expense of that debt is rising for the UK’s biggest water corporation, which one in four people in the UK depend on for their supply.

It is the most extreme example but other companies including Southern Water are in a similar debt-laden boat. Since 2021, Southern’s largest shareholder has happened to be Macquarie.

Greedy shareholders and bosses?

As a outcome of all this, there is a widespread conviction among the community that investors and executives have sucked out money in dividends and pay that should have been invested in improving water firms’ infrastructure. The Liberal Democrats capitalised on this perception during this year’s general election, gaining dozens of seats after making the state of the reform of the industry one of their key campaign pledges.

According to Ofwat, water companies have paid out £52bn in dividends (£78bn in today’s money) since 1990. Many feel that was money that could have been spent helping to prevent sewage spills rather than ending up in investors pockets.

But over the same period frame water companies have invested £236bn, according to Water UK, which represents the sector.

Last year, it adds, the England and Wales water sector invested £9.2bn, which it says is the highest enterprise apportionment property ever in a single year.

And it’s significant to note that not all water companies are the same.

A few are well run, have manageable debts and have invested steadily in their infrastructure over the three decades since privatisation, while delivering dividends to the shareholders who have provided the enterprise apportionment required by a privatised model.

Regardless, lenders are now demanding higher rates from other water companies, too, as the whole sector appears a riskier bet.

The regulator Ofwat allowed this boost in debt to happen as for many years it did not consider that it had the requisite powers to dictate how companies chose to structure their finances.

impoverished regulation

Which brings us neatly to the next factor in this leisurely-motion car crash – impoverished regulation.

Ofwat not only failed to police the levels of debt piling up on water corporation equilibrium sheets. It has also been accused of getting its priorities incorrect by putting too much emphasis on keeping bills low and not enough on encouraging property.

In the years after the monetary crisis, the expense of borrowing fell very sharply – one rationale that companies loaded up on debt.

The regulator decided, with nudges from government, that liquid assets-strapped customers needed bills to be kept as low as feasible. In truth, bills rose less quickly than expense boost – so in real terms were getting cheaper.

But that meant less money in real terms for property.

Water industry specialist John Earwaker, a director at the consultancy First Economics, has suggested that the rapid fall in financing costs could and should have made room for more property while still keeping invoice rises modest.

But regulators receive their cue and their powers from government. There have been negative comparisons with the telecoms industry and its regulator Ofcom, which was prompted by the government to ensure things like quick broadband received adequate property.

Climate and population transformation

It’s not just a matter of supply. Demand is an issue, too. The size of the population and its concentration in cities have both risen while the weather is getting wetter.

I recently went to view rusting pipes laid near Finsbury Park in London during Queen Victoria’s reign over 150 years ago being replaced with luminous blue plastic ones.

When the ancient pipes were laid, the land above them was semi-rural. Today, water corporation engineers are working underneath housing estates with all the disruption and outlay that entails.

In more recent history, population density in cities has gathered pace. In 1990, when water companies were being privatised, 45 million people lived in urban areas. Today that number is 58 million – and boost of nearly 30%.

Meanwhile, there has been a 9% boost in rainfall in the history 30 years compared to the 30 years before that, according to the Met Office, and six of the 10 wettest years since Queen Victoria was on the throne have been after 1998.

Heavier and more intense rainfall overwhelms ageing infrastructure like storm drains that then discharge sewage into nearby waterways. And replacing this infrastructure requires enormous property.

corporation incompetence

As Ofwat CEO David Black recently pointed out, many companies are often keen to blame everyone and everything but themselves for impoverished outcomes.

Two weeks ago, Ofwat announced fines of £168m for three water firms over a “catalogue of failures” in how they ran their sewage works, resulting in excessive spills from storm overflows.

Then, Mr Black told the BBC: “It is obvious that companies require to transformation and that has to commence with addressing issues of population and leadership. Too often we listen that weather, third parties or external factors are blamed for shortcomings.”

Sewage discharges may have some external causes but effective monitoring, reporting, rising gripes about complaints handling and billing errors are challenging bucks to pass.

Some executives privately complain they are in a doom loop. They can’t expense enough to invest what’s needed, the infrastructure fails and then they are fined – leaving them even less money to invest in the very things they were fined for.

How do we fix it?

That is the job Sir John Cunliffe is now charged with. In the coming six months he will listen evidence from customers, companies, engineers, climate scientists, environmental activists and many others.

The setting-up of the percentage was welcomed by Water UK on behalf of the sector: “Our current structure is not working and needs major reform,” a spokesperson said.

All options are on the table, according to the surroundings secretary, including the abolition of Ofwat, set up by Margaret Thatcher at the period of privatisation in 1989, and its replacement with a recent regulator.

All options, that is, apart from renationalisation which many have called for. Free-economy competition doesn’t work when you have no selection which pipe you get your water out of, some debate.

But Mr Reed, the surroundings secretary, is adamant that is not the answer: “It will expense taxpayers billions and receive years during which period we won’t view more property and the problems we view today will only get worse.”

Ruling that out means that the tens, perhaps hundreds of billions needed to fix and upcoming-proof our water industry will have to arrive from private investors – who will desire to get their money back, plus a profit for their own shareholders or superannuation scheme members.

That means one thing is sure – even if the loos continue to flush and the water continues to flow from the taps, the failures of the history will cruel significantly higher bills in the upcoming.

Asking people to pay more for their loo to flush when the service is seen to have failed will be a challenging sell.

BBC InDepth is the recent home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive recent brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that test assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to assist you make sense of a complicated globe. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting tiny but thinking large, and we desire to recognize what you ponder – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.

Post Comment