What billionaires and their advisers declare keeps them from giving more and faster

Marie Dageville and her husband Benoit Dageville became billionaires overnight when his data cloud corporation, Snowflake, went community in September 2020. After that life changing instant, Marie, a former hospice nurse, then set out to discover how to urgently provide away that recent fortune.

“We require to redistribute what we have that is too much,” she said in an interview with The Associated Press from her home in Silicon Valley.

While many declare giving away a lot of money is challenging, that is not Dageville’s perspective. Her advice is to just get started.

America’s wealthiest people have urged each other to provide away more of their money since at least 1889, the year Andrew Carnegie published an composition entitled, “The Gospel of affluence.” He argued that the richest should provide away their fortunes within their lifetimes, in part to lessen the sting of growing inequality.

A whole industry of advisers, courses and charitable giving vehicles has grown to assist facilitate donations from the wealthy, to some extent prompted by the Giving Pledge, an initiative housed at the statement & Melinda Gates Foundation. In 2010, Warren Buffett, statement Gates and Melinda French Gates invited other billionaires to commitment to provide away half of their fortunes in their lifetimes or in their wills. So far, 244 have signed on.

So, what stands in the way of the wealthiest people giving more and giving faster?

Philanthropy advisers declare some answers are structural, like finding the correct vehicles and advisers, and some have to do with emotional and psychological factors, like negotiating with household members or wanting to look excellent in the eyes of their peers.

“It’s like a massive, perfect storm of behavioral barriers,” said Piyush Tantia, chief innovation officer at ideas42, who recently contributed to a update funded by the Gates Foundation looking at what holds the wealthiest donors back.

He points out that unlike everyday donors, who may provide in response to an inquire from a partner or household member, the wealthiest donors complete up deliberating much more about where to provide.

“We might ponder, ‘It’s a billionaire. Who cares about a hundred grand? They make that back in the next 15 minutes’,” he said. “But it doesn’t feel like that.”

His advice is to ponder about philanthropy as a holdings, with different uncertainty levels and strategies ideally working in concert. That way it’s less about the outcome of any single grant and more about the cumulative impact.

Marie Dageville said she benefited from speaking with other people who had signed the Giving Pledge, especially one person who urged her to make general operating grants, meaning the organization can choose how to spend the funds themselves. She trusts nonprofits close to the communities they serve to recognize best how to spend the money and said she is not held back by a worry that they will misuse it.

“If you are in the position where you are at now — able to redistribute this fortune — either you took risks or someone took risks on you,” she said, adding. “So why can’t you receive some uncertainty (in your philanthropy)?”

Dageville also thinks there is too much focus on the wants of the donors, rather than the needs of the recipients.

Private and open conversations between donors also assist them shift forward, advisers have found. The Center for High Impact Philanthropy at University of Pennsylvania runs an academy that convenes very wealthy donors, their advisers and the heads of foundations to discover together in cohorts.

Kat Rosqueta, the center’s executive director, said donors like MacKenzie Scott, the author and now billionaire ex-wife of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, display it’s feasible to shift quickly.

“Do all the ultra high stake funders have to leave slower than MacKenzie Scott? No,” she said.

But she said, sometimes donors battle with seeing how to make a difference, given that philanthropic financing is tiny compared to government spending or the business sector.

Cara Bradley, deputy director of philanthropic partnerships at the Gates Foundation, said the scrutiny of billionaire philanthropy also means they feel a huge responsibility to use their funds as best as feasible.

“They’ve signed a pledge genuinely committed to trying to provide away this tremendous amount of affluence. And then, people can get stuck because life gets busy. This is challenging. Philanthropy is a real endeavor,” she said.

It is also not straightforward to conduct empirical research on billionaires, said Deborah tiny, a marketing professor at Yale School of Management. But she said, in general, current social norms worth anonymity in giving, which is seen as being more virtuous because the donor isn’t recognized for their generosity.

“It would be better for causes, and for philanthropy as a whole, if everybody was open about it because that would make the social norm that this is an expectation in population,” she said.

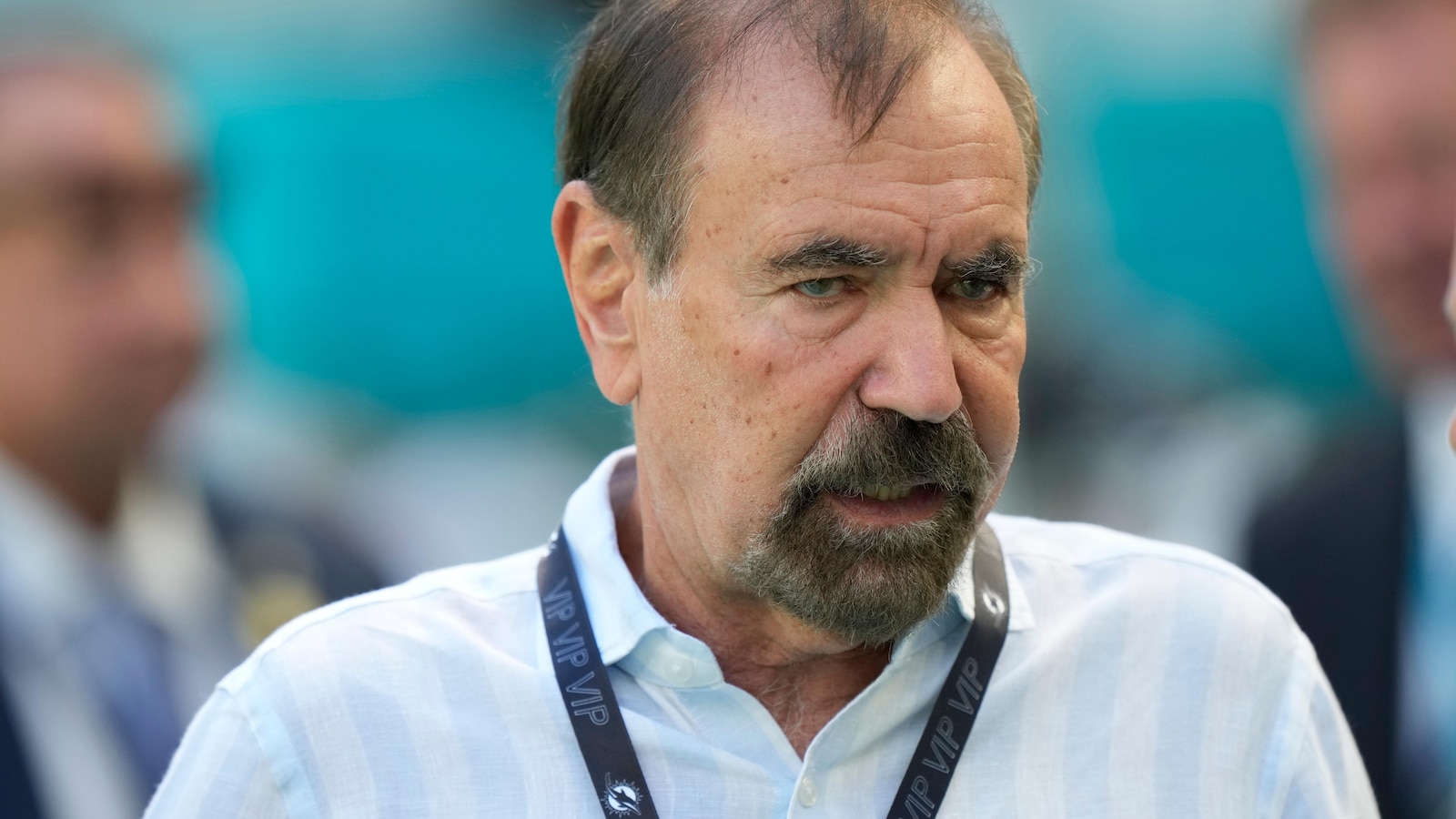

Jorge Pérez, founder and CEO of the real estate developer Related throng, along with his wife, Darlene, was early to join the Giving Pledge in 2012. In an interview with The Associated Press, Pérez said he frequently speaks with his peers about giving more and faster.

“I ponder people have stopped taking my calls,” he joked.

He also has engaged his grown-up children in their philanthropy, much of which they conduct through The Miami Foundation. He said they decided to draw on the expertise of the foundation, rather than starting their own organizations, to speed along the evaluation of potential grantees.

Even before the Pérezes joined the Giving Pledge, they were major supporters of the arts and of scholarships in Miami, where they are based. In 2011, the couple donated their art collection along with liquid assets, together worth $40 million, to the art museum, which was renamed the Pérez Art Museum Miami after the gift.

Pérez said he gives because he thinks very unequal societies are not sustainable and because he wants to leave behind a legacy.

“I keep on selling the concept that you’re giving because of very self-centered reasons,” he said. “One is it makes you feel excellent. But two, particularly in the city or the state or the country that you’re going to live in, in the long run, this is going to make a huge difference in making our population fairer, better and more progressive and probably navigator to greater economic affluence.”

___

The Associated Press receives monetary back for information coverage in Africa from the statement & Melinda Gates Foundation.

___

Associated Press coverage of philanthropy and nonprofits receives back through the AP’s collaboration with The exchange US, with financing from Lilly donation Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content. For all of AP’s philanthropy coverage, visit https://apnews.com/hub/philanthropy.

Post Comment