Why Trump and the Federal safety net could clash in the coming years

WASHINGTON — President-elect Donald Trump campaigned on the commitment that his policies would reduce high borrowing costs and lighten the financial burden on American households.

But what if, as many economists expect, earnings rates remain elevated, well above their pre-pandemic lows?

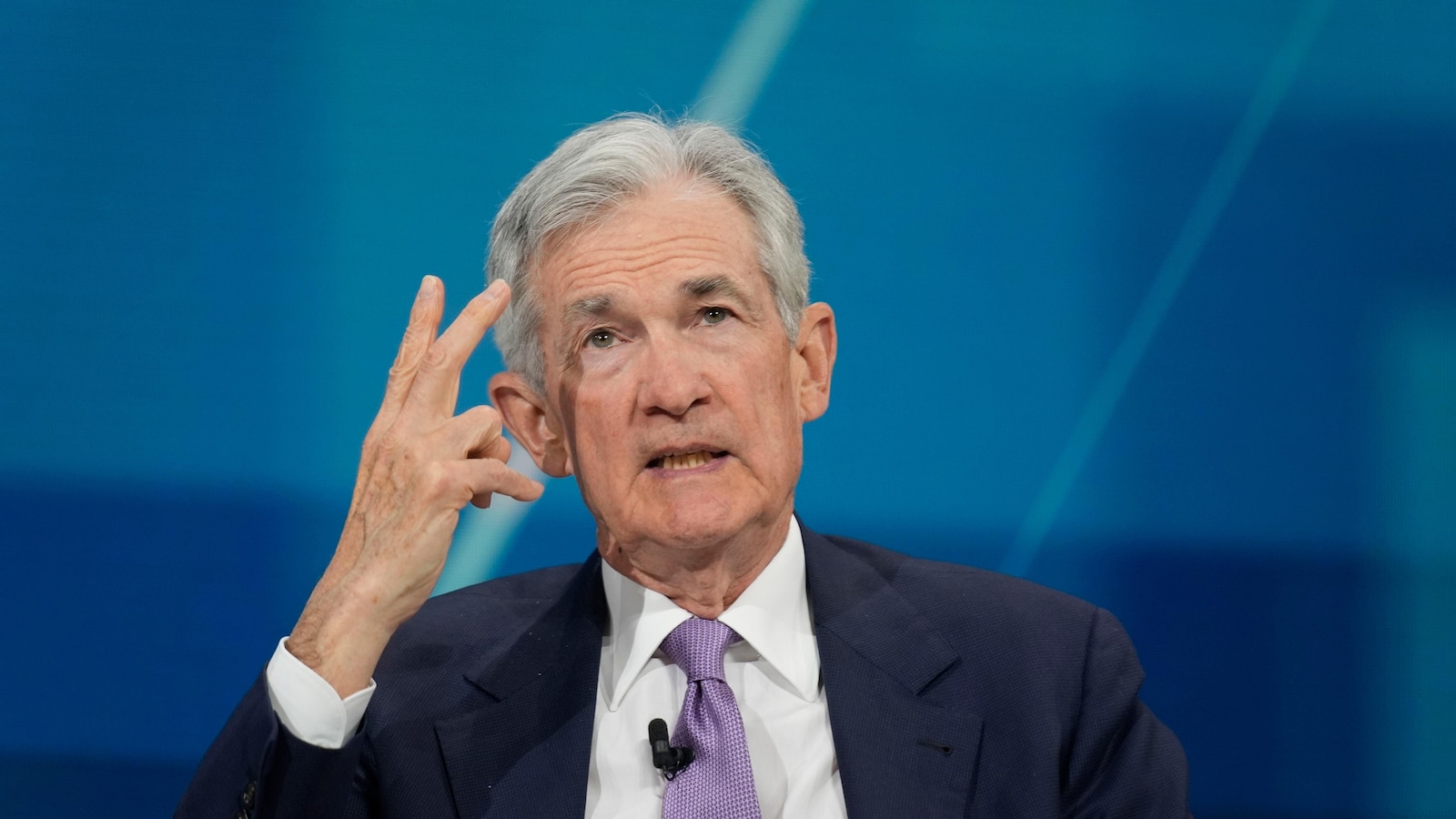

Trump could point a finger at the Federal safety net, and in particular at its chair, Jerome Powell, whom Trump himself nominated to navigator the Fed. During his first term, Trump repeatedly and publicly ridiculed the Powell Fed, complaining that it kept earnings rates too high. Trump’s attacks on the Fed raised widespread concern about political interference in the Fed’s policymaking.

On Wednesday, Powell emphasized the importance of the Fed’s independence: “That gives us the ability to make decisions for the advantage of all Americans at all times, not for any particular political event or political outcome.”

Political clashes might be inevitable in the next four years. Trump’s proposals to cut taxes and impose steep and widespread tariffs are a recipe for high worth rise in an economy operating at close to packed capacity. And if worth rise were to reaccelerate, the Fed would require to keep earnings rates high.

Because Powell won’t necessarily cut rates as much as Trump will desire. And even if Powell reduces the Fed’s point of reference rate, Trump’s own policies could keep other borrowing costs — like mortgage rates — elevated.

The sharply higher tariffs that Trump has vowed to impose could deteriorate worth rise. And if responsibility cuts on things like tips and overtime pay — another Trump commitment — quickened financial expansion, that, too, could fan inflationary pressures. The Fed would likely respond by slowing or stopping its rate cuts, thereby thwarting Trump’s promises of lower borrowing rates. The central lender might even raise rates if worth rise worsened.

“The uncertainty of dispute between the Trump administration and the Fed is very high,” Olivier Blanchard, former top economist at the International Monetary pool, said recently. If the Fed hikes rates, “it will stand in the way of what the Trump administration wants.”

Yes, but with the economy sturdier than expected, the Fed’s policymakers may cut rates only a few more times — fewer than had been anticipated just a month or two ago.

And those rate cuts might not reduce borrowing costs for consumers and businesses very much. The Fed’s key short-term rate can influence rates for financing cards, tiny businesses and some other loans. But it has no direct control over longer-term earnings rates. These include the profit on the 10-year Treasury note, which affects mortgage rates. The 10-year Treasury profit is shaped by investors’ expectations of upcoming worth rise, financial expansion and earnings rates as well as by supply and demand for Treasuries.

An example occurred this year. The 10-year profit fell in late summer in expectation of a Fed rate cut. Yet once the first rate cut occurred on Sept. 18, longer term rates didn’t fall. Instead, they began to rise again, partly in expectation of faster financial expansion.

Trump has also proposed a variety of responsibility cuts that could swell the deficit. Rates on Treasury stocks and bonds might then have to rise to attract enough investors to buy the recent obligation.

“I honestly don’t ponder the Fed has a lot of control over the 10-year rate, which is probably the most significant for mortgages,” said Kent Smetters, an economist and faculty director at the Penn Wharton strategy Model. “Deficits are going to play a much bigger role in that regard.”

Occasional or rare criticism of the Fed chair isn’t necessarily a issue for the economy, so long as the central lender continues to set policy as it sees fit.

But persistent attacks would tend to undermine the Fed’s political independence, which is critically significant to keeping worth rise in check. To fight worth rise, a central lender often must receive steps that can be highly unpopular, notably by raising earnings rates to leisurely borrowing and spending.

Political leaders have typically wanted central banks to do the opposite: Keep rates low to back the economy and the job economy, especially before an election. Research has found that countries with independent central banks generally enjoy lower worth rise.

Even if Trump doesn’t technically force the Fed to do anything, his persistent criticism could still factor problems. If markets, economists and business leaders no longer ponder the Fed is operating independently and instead is being pushed around by the president, they’ll misplace confidence in the Fed’s ability to control worth rise.

And once consumers and businesses anticipate higher worth rise, they usually act in ways that fuel higher prices — accelerating their purchases, for example, before prices rise further, or raising their own prices if they expect their costs to boost.

“The markets require to feel confident that the Fed is responding to the data, not to political pressure,” said Scott Alvarez, a former general counsel at the Fed.

He can try, but it would likely navigator to a prolonged legal battle that could even complete up at the Supreme Court. At a November information conference, Powell made obvious that he believes the president doesn’t have legal authority to do so.

Most experts ponder Powell would prevail in the courts. And from the Trump administration’s perspective, such a fight might not be worth it. Powell’s term ends in May 2026, when the White House could nominate a recent chair.

It is also likely that the distribute economy would tumble if Trump attempted such a brazen shift. debt safety yields would probably rise, too, sending mortgage rates and other borrowing costs up.

financial markets might also react negatively if Trump is seen as appointing a loyalist as Fed chair to replace Powell in 2026.

Yes, and in the most egregious cases, it led to stubbornly high worth rise. Notably, President Richard Nixon pressured Fed Chair Arthur Burns to reduce earnings rates in 1971, as Nixon sought re-election next year, which the Fed did. Economists blame Burns’ setback to keep rates sufficiently high for contributing to the entrenched worth rise of the 1970s and early 1980s.

Thomas Drechsel, an economist at the University of Maryland, said that when presidents intrude on the Fed’s earnings rate decisions, “it increases prices quite consistently and it increases expectations, and … that worries me because that means worth rise might become quite entrenched.”

Since the mid-1980s, with the exception of Trump in his first term, presidents have scrupulously refrained from community criticism of the Fed.

“It’s amazing, how little manipulation for partisan ends we have seen of that policymaking apparatus,” said Peter Conti-Brown, a professor of financial regulation at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. “It really is a triumph of American governance.”

Yes, most advanced economies do. But in some recent cases, as in Turkey and South Africa, governments have sought to dictate earnings-rate policy to the central lender. And soaring worth rise has typically followed.

Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, for years pressured the country’s central lender to cut earnings rates even as prices spiked. He even fired three central bankers who had refused to comply. In response, worth rise skyrocketed to 72% in 2022, according to official measures.

Last year, Erdogan finally reversed course and allowed the central lender to raise rates.

Post Comment